Dispatch from Shanghai

What does independent publishing look like outside the big hubs like London and New York? Our monthly series turns to special correspondents in some of the world’s most interesting centres of independent publishing to get the view from the ground. This month, the artist known as Boihugo reports on the magazines coming out of Shanghai, China.

Shanghai, September 2020 –– It is steamy, sticky; humid to the point of mild suffocation, and I am standing inside the abC (art book in China) fair, which hosts 139 artists, illustrators, art bookstores, design studios and a small but vital contingent of independent magazine publishers. The sheer number of people in this building is insane. The scrum is testament to a local publishing scene that is thriving. Due to the strict quarantine imposed by Premier Li Keqiang’s government in the wake of coronavirus, the exhibitors at this fair, unlike previous years, are predominantly Chinese.

I moved back to Shanghai a little over a year ago after finishing art school in London. Partly that was because I was attracted by the active magazine-making community. But living and working here hasn’t been as smooth sailing as I had anticipated. Exhibiting the queer fashion magazine I co-direct, untitled folder, at another a book fair in the city this October, I was warned to hide it when representatives from the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) looked round. I was also advised to change my outfit to something more straight-appearing — I was wearing a neon green sweatshirt at the time.

I had dreams about being arrested that night. I dream about that a lot, making a magazine in Shanghai. It’s a paranoia shared by my fellow publishers, even those who are not working with ‘sensitive issues’ such as sexualities or queer politics. There is almost no way for a non-state owned publisher to get an ISBN, giving the government an exceptional level of control over printed material. Any criticism of the government will attract attention, as will LGBT content.

In Shanghai, stores for art books and independent magazines are rare. High-end clothing shops and cafes are the only offline spaces where you can pick up magazines; state censors turn a blind eye to magazines sold in lifestyle stores because shops like these are considered harmless and they contribute a lot of tax revenue. To publish a magazine in Shanghai is to walk a very thin line: 3-day book fairs such as abC and UNFOLD that happen annually in the city between May and October provide the manageable amount of exposure that we need; not so much that we attract attention from government authorities, not so little that the only people reading us are ourselves.

The magazines I have selected to showcase Shanghai’s indie-scene are predominantly printed in English with a few printed bilingually. Some claim that in this way, the chance of being reported is lessened, as you won’t become too widely read if you don’t print in Chinese. But of course, excluding those who can’t speak English brings its own problems, as it makes the audience class-based.

The print runs of these magazines are small with no exceptions, ranging from 300 to 1000 copies. Almost no one here makes a living by independent publishing — when money is not the main driving force, conflict and competition melts away, and what you’re left with is a scene that values genuine curiosity.

The community of creatives in Shanghai are unusual in that they are borderless. It is typical to go away to study as a young Chinese person, or to do a residency or gig abroad. I have faith that when all this is over, Shanghai’s creative community will be able to travel freely again. The energy generated from the creative youth mobility makes our magazine scene richer. What I find remarkable about all these publications is their dedication to their city. We are dedicated to reshaping Shanghai’s cultural landscape. We move away but we always come home.

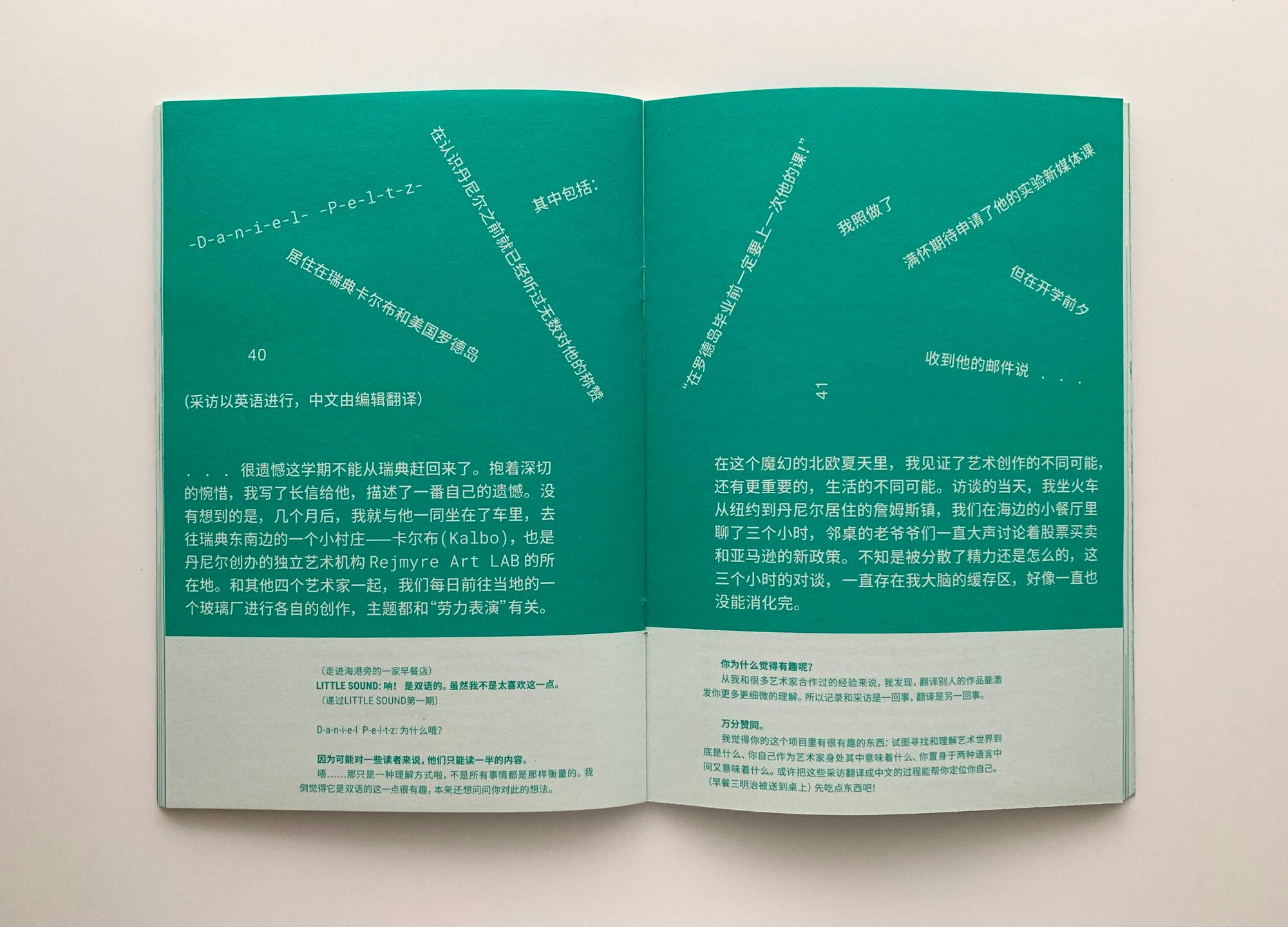

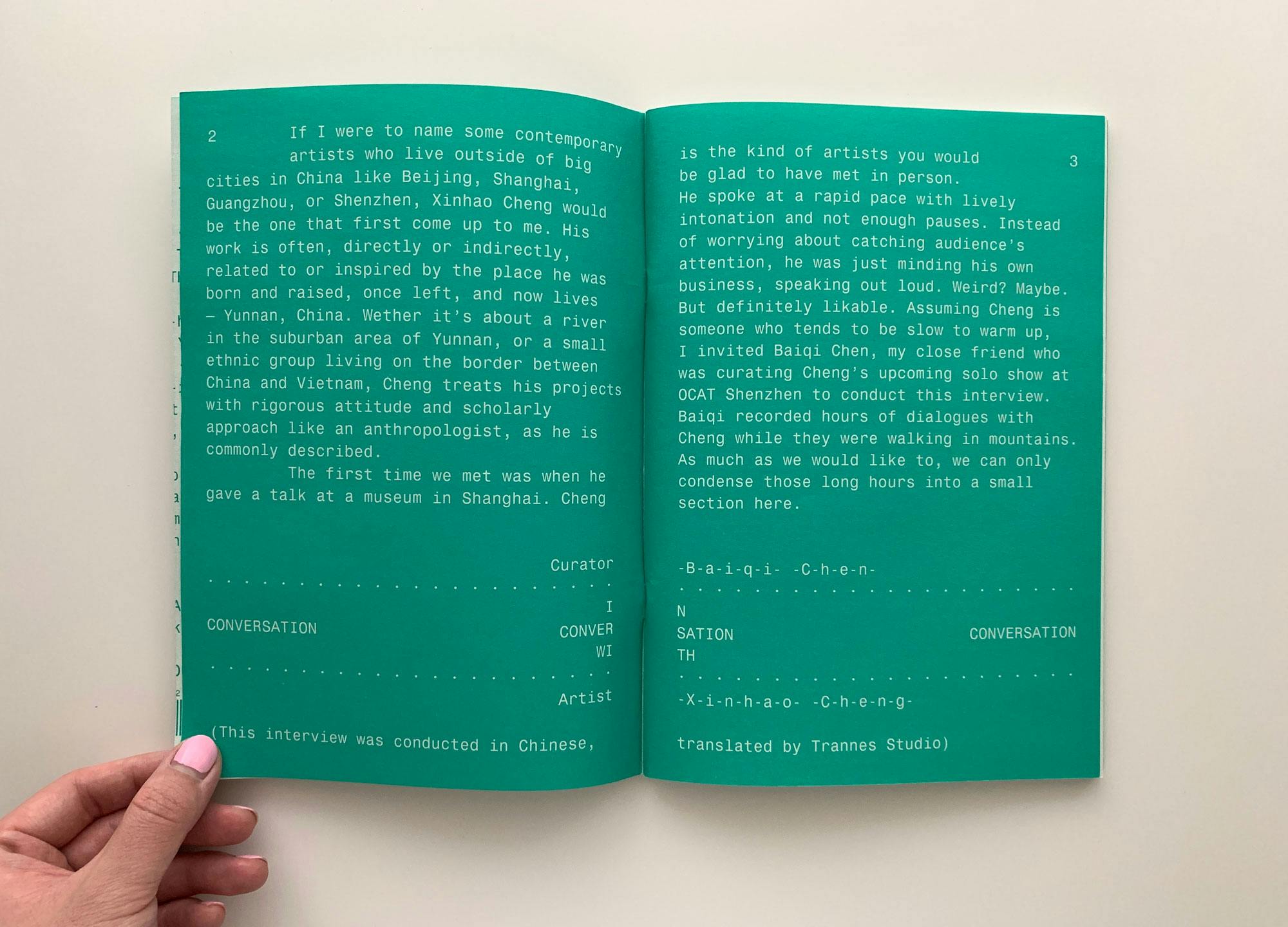

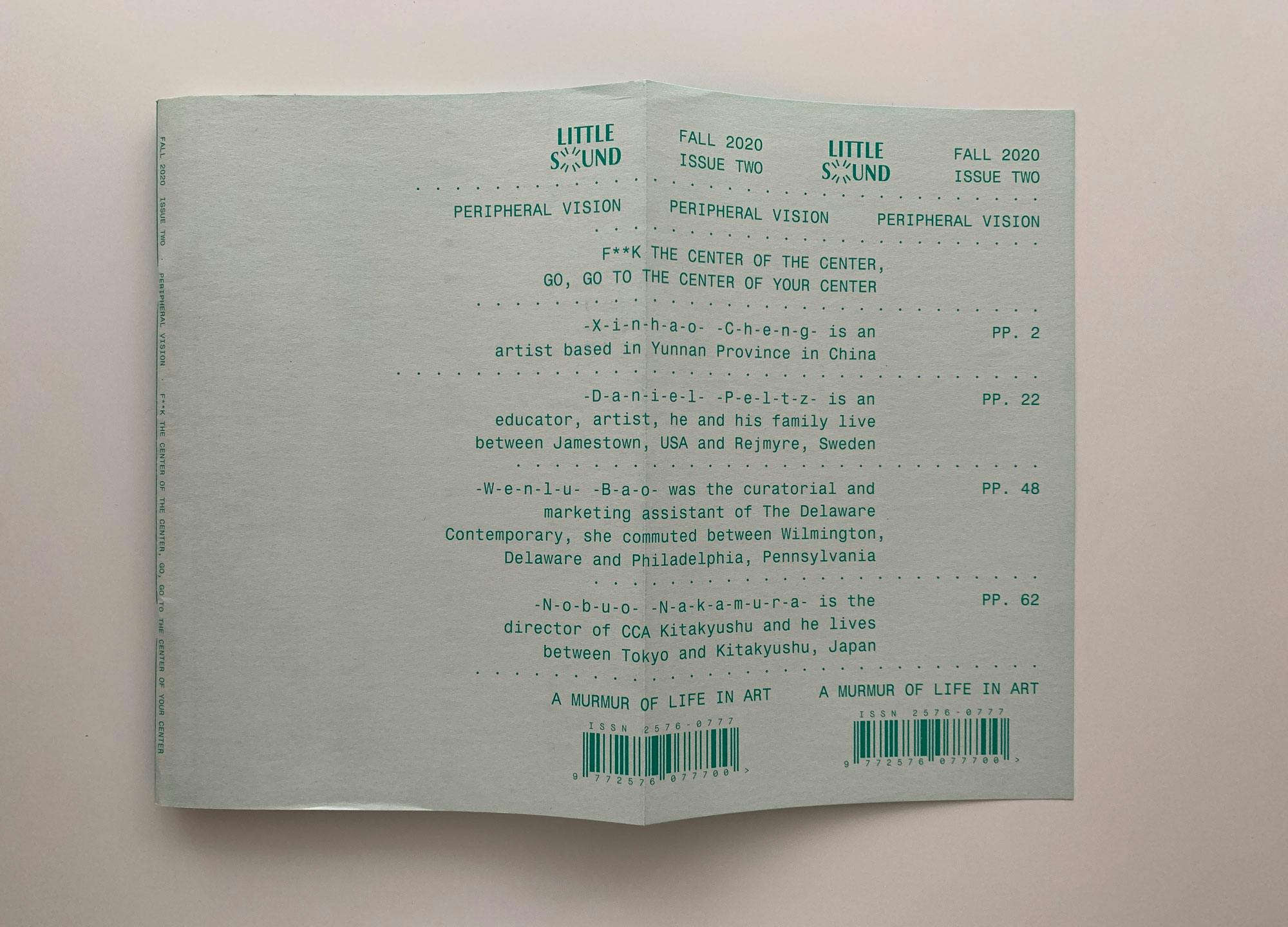

Little Sound (which they print in caps, LITTLE SOUND) opens with a bold statement: “F**K THE CENTER OF THE CENTER, GO, GO TO THE CENTER OF YOUR CENTER”. A text-only English and Chinese bilingual magazine, Little Sound was founded to amplify “the murmurs of life in art”. Reading a magazine without any pictures was not as hard as I imagined, because Little Sound’s content is interview-based, and remarkably cozy and intimate — it did feel like someone sat and murmured in my ear.

Focusing on the art practitioners living and working outside the traditional ‘centres’, editor-in-chief Jasphy Yiran Zheng told me via email that this issue was born out of her decision to move to Songjiang, Shanghai from New York City for six months, attracted by the emerging artist community here. The rent is relatively low as it’s far from the city centre, which promises greater freedom to residents, who consist of a mixture of local artists and recent art graduates from the West.

In one of my favourite pieces, educator and artist Daniel Pelts shared inspiring thoughts on temporality and community, peripheral and central experiences, as well as “having time” and “having another kind of ‘time’ that can only exist if you have that time”. I spent a night reading this lovely magazine in my tiny apartment in central Shanghai, and felt refreshed.

Buy Little Sound in the Stack shop

I should say upfront that I am the features director of Untitled Folder magazine, which was founded by Edge Yang. I joined him in Shanghai to create issue 05, which shifts focus towards domestic queer discourse, while still maintaining the goal of being a “small but specific” bridge between the Eastern and Western queer worlds.

The theme of fifth issue is ‘alternative means of (queer) resistance’. Edge created a section called Chinese Queer Gods, meant to challenge the accepted wisdom that all Gods in China, both Christian and Buddhist, are heteronormative. Our Global Oriental Queer Association welcomed six new members; a former-solider-and-all-time-Chinese-queer modelled ‘post-quarantine rave looks’, accompanied by a think piece on the alternative artsy queer nightlife scenes of Beijing and Shanghai.

Design-wise, this issue features a ‘hard cover with a harder spot’, which was proposed by graphic designer Gao Han in response to the themed content. The small metal spot between the hardcover and the cloth finishing could be interpreted as a life-sized nipple, as it pretty much looks like one. The more you touch it, the darker it gets. It is also a sweet little spot that you can easily rest your finger on or play with while reading the publication.

Buy Untitled Folder in the Stack shop

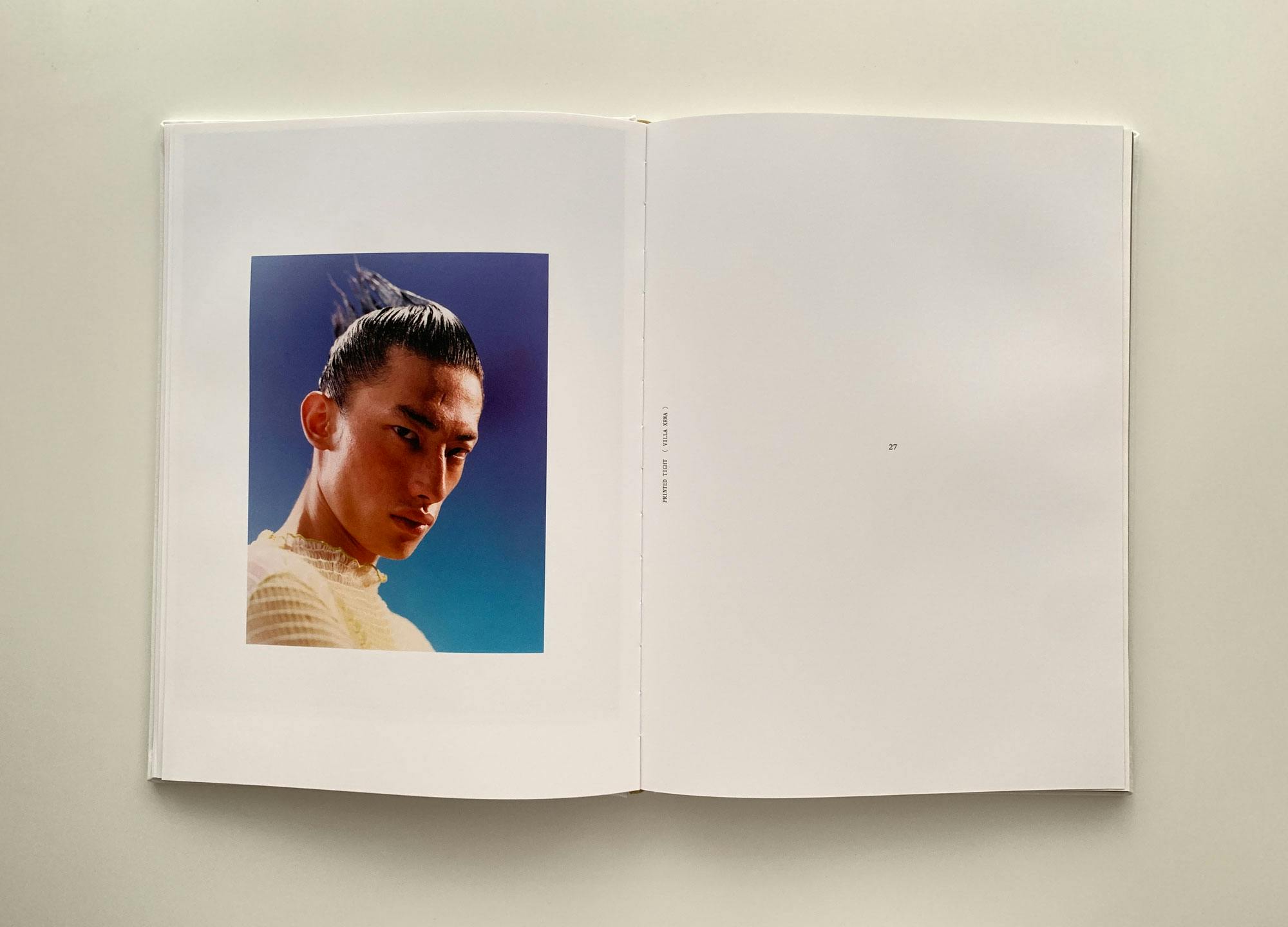

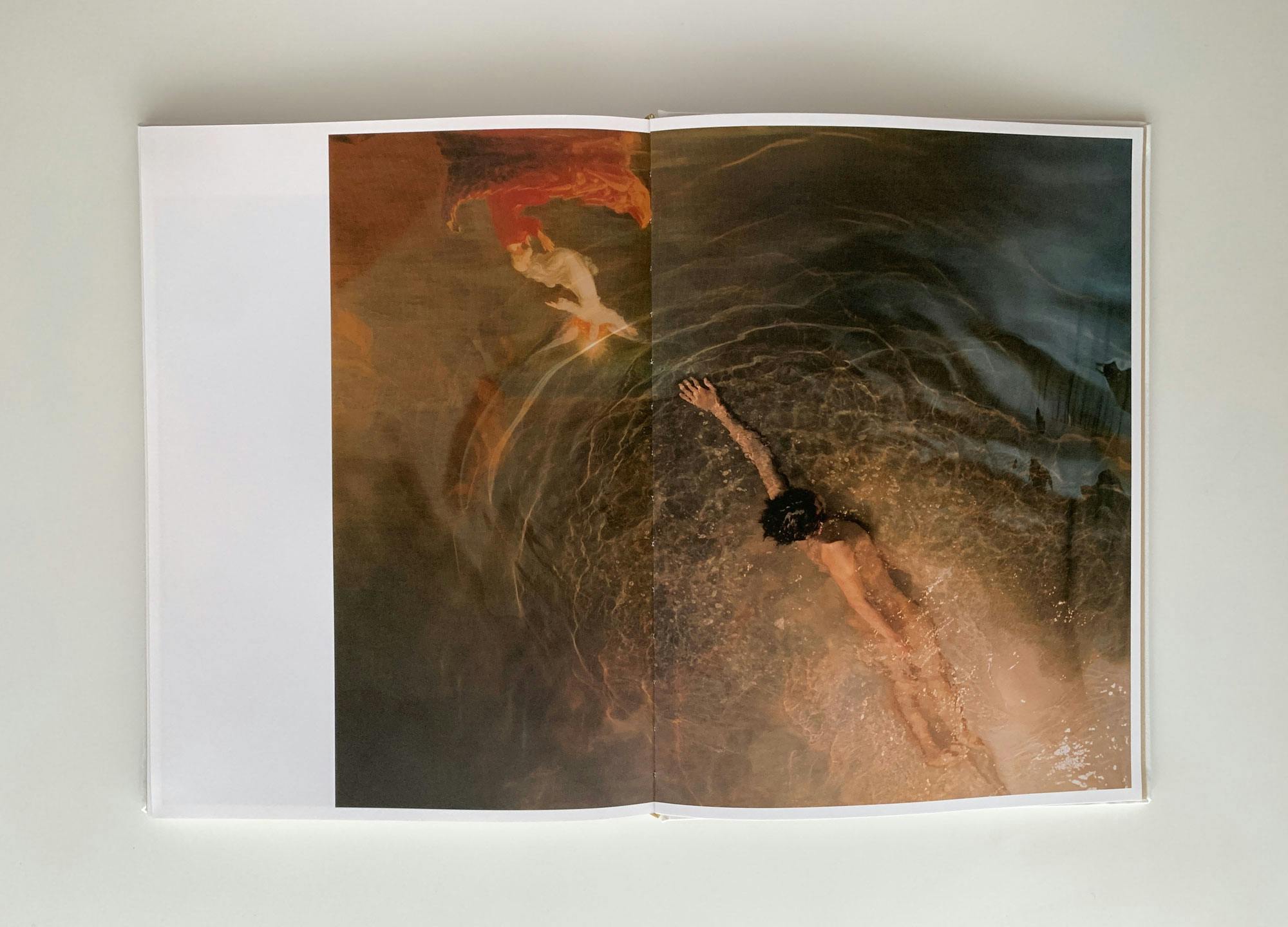

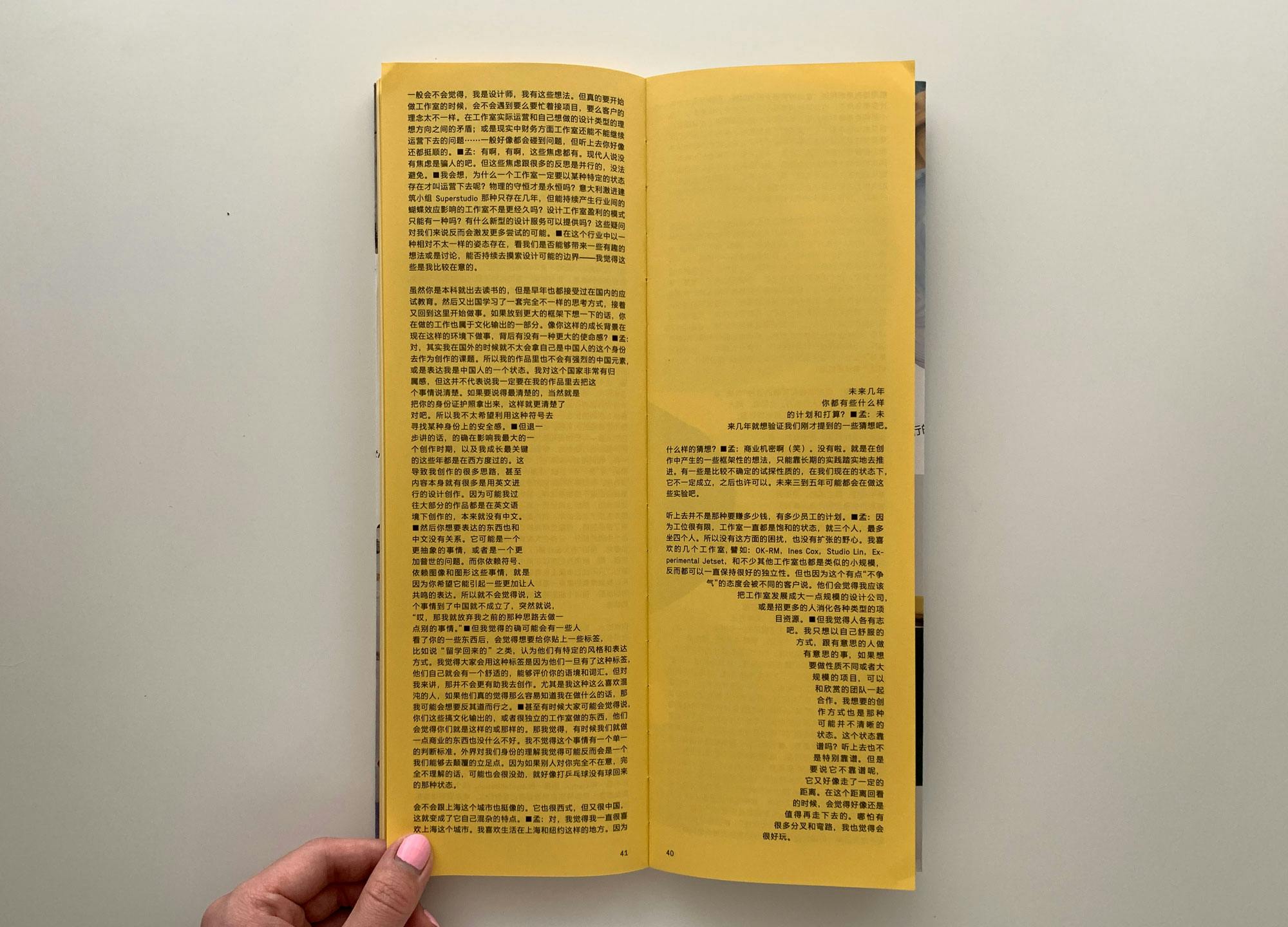

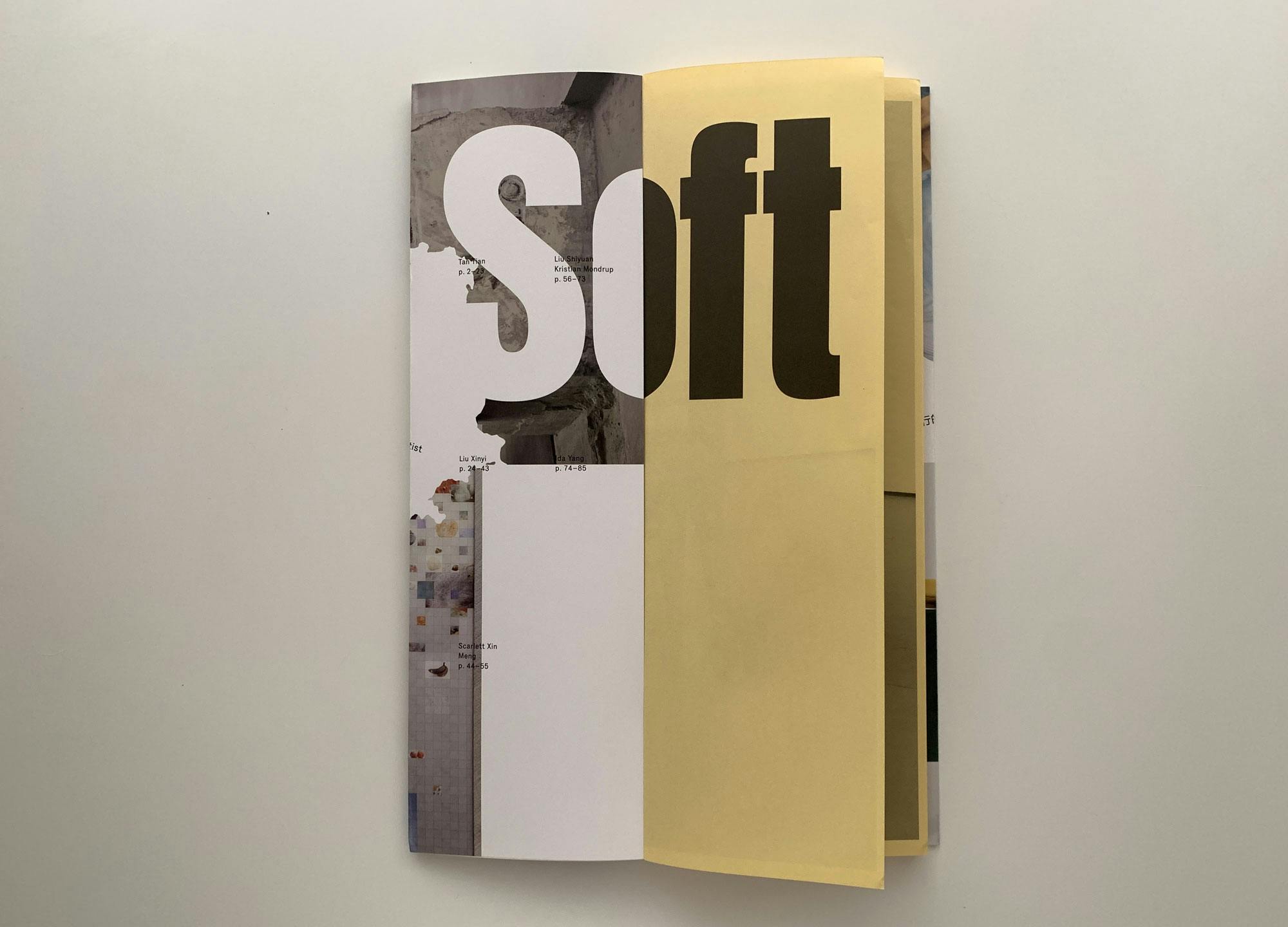

Soft — written [soft] — was founded by editor Zoe Chen in the leafy French Concession area of Shanghai. Although Chen now lives in the USA, the area and its dense creative population continue to be her inspiration for the magazine. In the latest issue, Soft’s fifth, the magazine focuses on young and predominantly Chinese artists who actively travel(ed) in between cultures, some as former international students, some as creative workers or emerging artists.

The interviews were mainly conducted before the pandemic with some dated back to three years ago and re-edited recently, but the ideas are not outdated at all; the words ‘globalisation’ and ‘de-globalisation’ appear repeatedly in conversations, which feels more relevant than ever now, when borders are closed and global travel is endangered.

In Shanghai, travel restrictions for residents are currently subtle but effective: you can still go abroad, but it is difficult to come back; air tickets are scarce and overpriced, plus you have to get two negative corona test results in an almost impossibly tight deadline, and self-fund a 14-day hotel quarantine on your return. Reading texts from the ‘normal’ past while being physically stuck in Shanghai, I had mixed feelings. It gave me a glimpse of the literal destruction of the dearly cherished ideal of being a ‘world citizen’, and made me rethink Eurocentrism and Sinocentrism. At the same time, it gave me a surreal and temporary feeling of escape.

Code 52 is a new magazine and curatorial platform that aims to create opportunities for cultural exchange. It is made in Shanghai, but editor Mharie Berger had to relocate to Berlin during the pandemic due to visa issues. The name refers to the magazine’s clear editorial structure: each issue features 5 cities, with 2 artists highlighted per city. The team is experienced: Berger used to work for o32c and creative consultant Boah Kim used to work for Balenciaga.

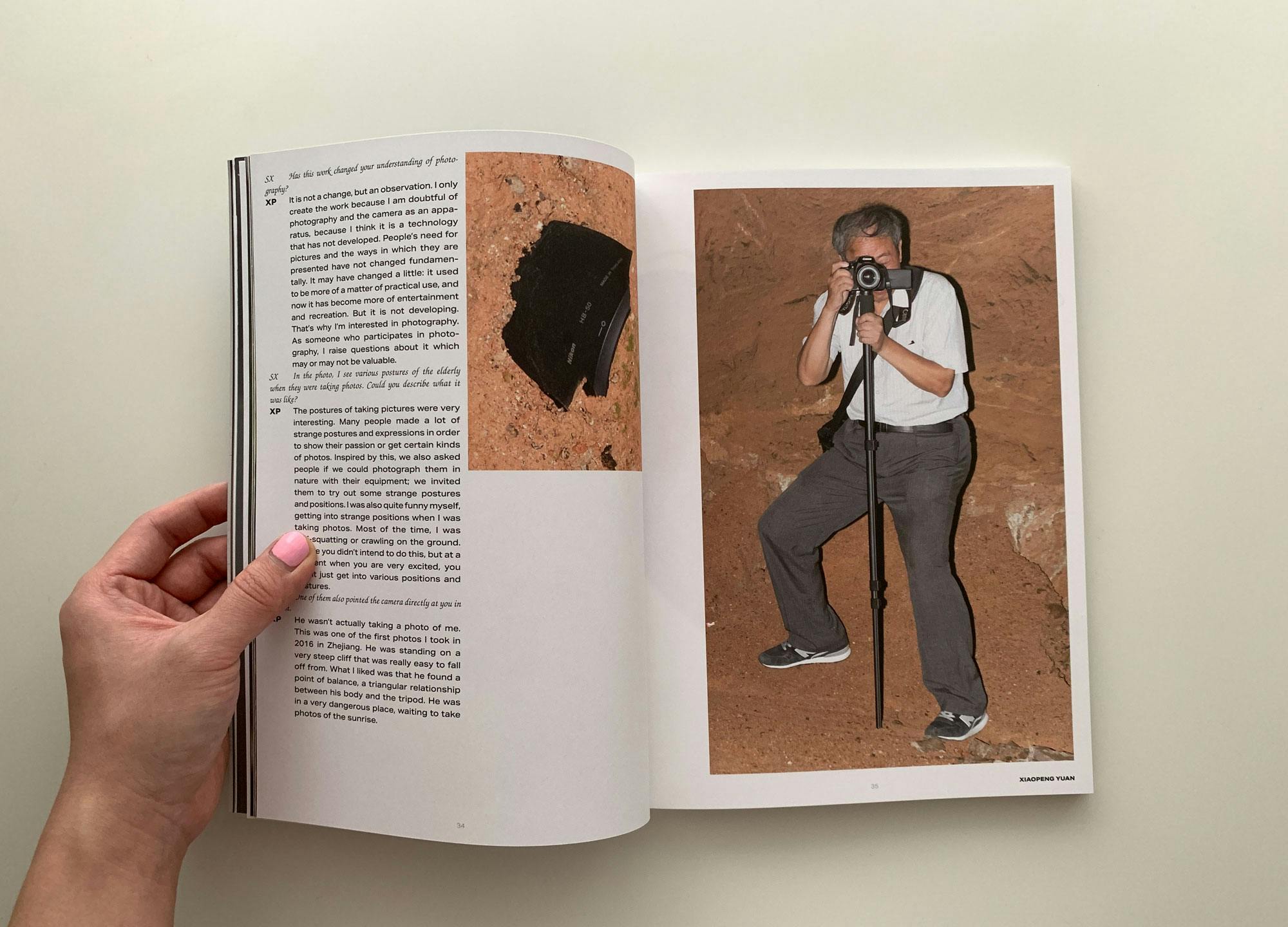

The launch issue features Shanghai, Mexico City, Taipei, Berlin and Paris. One of the visual stories is about SHCR (Shanghai Community Radio), which streamed 100 sessions with performers in the underground club and art world over lockdown as a way to offer comfort. In my favourite feature, photographer Xiaopeng Yuan captured a group of elderly nature photography lovers who risked their lives to capture a perfect image at a wetland park on the outskirts of Shanghai. Art director Chengxi Tian brought her Shanghainese grandma to the shoot in order to break into the group smoothly, which is pretty sweet.

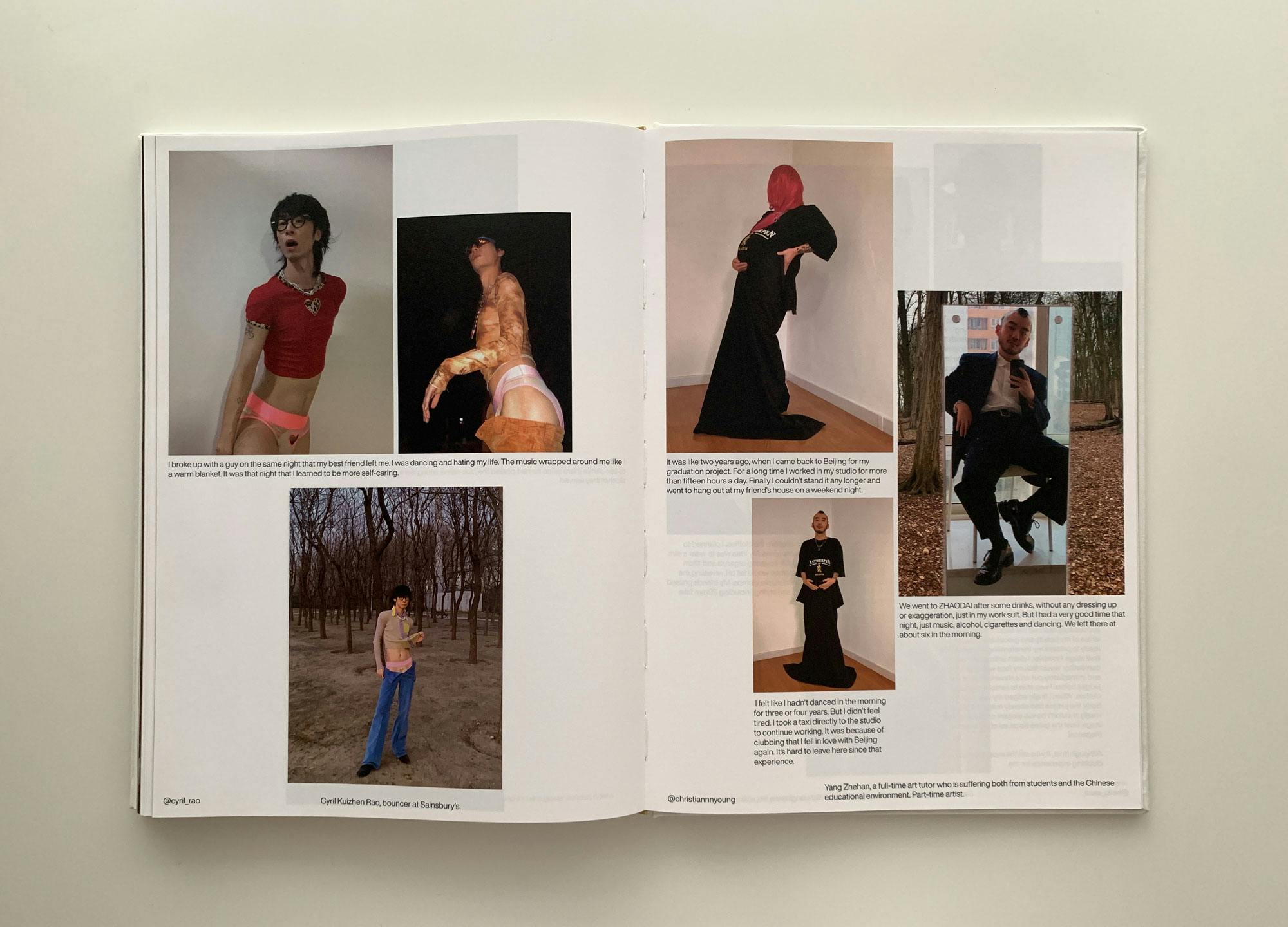

Co-edited by Beijing-based artist Ye Funa and Shanghai-based Curator Milia Xin Bi, Monday Off is a magazine about rapidly evolving youth culture in contemporary China. According to Milia, youth culture here is ‘wild, uncategorised, small, complicated and sentimental.‘ The culture feels like smoke: it appears and disappears suddenly, if you don’t document it soon enough, it will just be gone with the wind.

Medical Cosmetology is the theme of this latest issue, inspired by the flourishing cosmetic clinics and hospitals that have opened on almost every street in Shanghai in recent years. Even the magazine’s logo has undergone a corresponding plastic surgery, from pixelated frowning and winking faces, to frowning and winking faces in high resolution.

Featuring visual editorials, academic essays, and a glossary, Monday Off issue 2 looks and feels more like an ambitious curatorial experimentation or a ‘research as practice’ project than a magazine. Highlights include an essay by Enke Huang on transcending the traditional anthropological gaze, and a think piece by Zheng Peihan on the possibilities of counter-facial recognition practices. There is also a fascinating interview with Wang Buke, a former art school graduate who majored in sculpture but whose day job now includes practising cosmetic surgery on goat’s faces.